introduces :

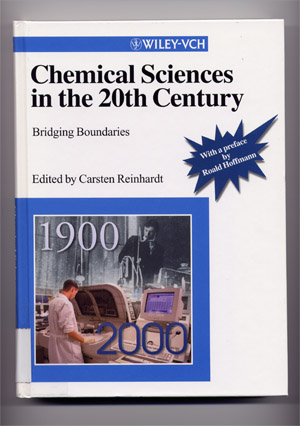

introduces :C. Reinhardt (ed.)

Chemical Sciences in the 20th Century

Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2001

ISBN 3-527-30271-9

EUR 89.00 about $90.00

introduces :

introduces :

Table of Contents

Foreword ................................................................ V

Roald Hoffmann

Preface ................................................................. IX

Christoph Memel

List of Contributors .................................................... XVII

Disciplines, Research Fields, and their Boundaries ...................... 1

Carsten Reinhardt

References and Notes .................................................... 13

1. Research Fields and Boundaries in Twentieth-Century Organic Chemistry ... 14

Peter J.T.Morris, Anthony S.Travis, and Carsten Reinhardt

1.1 Physical Organic Chemistry .............................................. 14

1.2 Physical Instrumentation and Organic Chemistry .......................... 20

1.3 Bioorganic Chemistry .................................................... 29

1.4 Conclusion .............................................................. 38

References and Notes .................................................... 38

Part I

Theoretical Chemistry and Quantum Chemistry

2. Theoretical Quantum Chemistry as Science and Discipline:

Some Philosophical Remarks on a Historical Issue ........................ 45

Nikos Psarros

2.1 The Quarrel of the Faculties ............................................ 45

2.2 Theoretical Quantum Chemistry: Establishing a New Science in the

Twentieth Century ....................................................... 46

2.3 Giovanni Battista Bonino: Pioneer of the New Science and Founder of a

New Discipline in Italy ................................................. 48

2.4 Jean Barriol: The French Version ........................................ 49

References and Notes .................................................... 50

3. Issues in the History of Theoretical and Quantum Chemistry, 1927-1960 ... 51

Ana Simoes and Kostas Gavroglu

3.1 Introduction ............................................................ 51

3.2 Re-thinking Reductionism or the Chemists' Uneasy Relation with

Mathematics ............................................................. 51

3.3 Convergence of Diverging Traditions: Physics, Chemistry, and

Mathematics ............................................................. 56

3.4 The Role of Textbooks in Building a Discourse for Quantum

Chemistry ............................................................... 62

3.5 The Ontological Status of Resonance ..................................... 64

3.6 The Status of the Chemical Bond ......................................... 68

3.7 The Impact of Computers in Quantum Chemistry: the Split of the

Community ............................................................... 70

References and Notes 72

4. Giovanni Battista Bonino and the Making

of Quantum Chemistry in Italy in the 1930s .............................. 75

Andreas Karachalios

4.1 Introduction ............................................................ 75

4.2 Early Career ............................................................ 76

4.3 Bonino and the Beginning of Infrared Spectroscopy in Italy .............. 77

4.4 The Scientific and Political Context .................................... 79

4.5 Scientific Contacts in Germany and Austria, 1931—1934 ................... 83

4.6 Early Contributions to Quantum Chemistry ................................ 86

4.7 Bonino's Place within Contemporary Research ............................. 89

4.8 The Advent of Group Theory in Bonino's Work ............................. 90

4.9 Bonino's Quantum Mechanical Concept of Coordination ..................... 92

4.10 Encroaching Political Developments ...................................... 94

4.11 Conclusion .............................................................. 98

References and Notes .................................................... 99

5. Between Disciplines: Jean Barriol and the

Theoretical Chemistry Laboratory in Nancy ............................... 105

Marika Blondel-Mégrelis

5.1 Inspirations ............................................................ 106

5.2 Mathematics ............................................................. 108

5.3 Quantum Chemistry ....................................................... 110

5.4 Pragmatism .............................................................. 111

5.5 Foundations ............................................................. 112

5.6 Experiment .............................................................. 114

5.7 Jean Barriol's Theoretical Chemistry .................................... 115

References and Notes .................................................... 117

Part II

From Radiochemistry to Nuclear Chemistry and Cosmochemistry

6. From Radiochemistry to Nuclear Chemistry and Cosmochemistry ............. 121

Xavier Roqué

6.1 Physical Evidence in Chemical Disciplines ............................... 122

6.2 Identification and Production ........................................... 124

6.3 Natural Versus Arfificial Elements ...................................... 126

6.4 Discipline Dynamics ..................................................... 127

References and Notes .................................................... 129

7. The Discovery of New Elements and the Boundary

Between Physics and Chemistry in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Case of Elements 43 and 75 .......................................... 131

Brigitte Van Tiggelen

7.1 Rhenium: A Success ...................................................... 132

7.2 A Failure: Masurium ..................................................... 137

7.3 A Comparison: From Hunting to Breeding .................................. 139

7.4 The End of a Research Tradition ......................................... 140

References and Notes .................................................... 142

8. The Search for Artificial Elements and the Discovery of Nuclear Fission . 146

Ruth Lewin Sime

References and Notes .................................................... 158

9. From Geochemistry to Cosmochemistry:

The Origin of a Scientific Discipline, 1915—1955 ........................ 160

Helge Kragh

9.1 Introduction ............................................................ 160

9.2 Nineteenth-Century Backgrounds .......................................... 161

9.3 Chemists, Element Formation, and Stellar Energy ......................... 164

9.4 Victor Moritz Goldschmidt and the Transition from Geo- to

Cosmochemistry .......................................................... 169

9.5 Geochemistry and the Shell Model of Nuclear Structure ................... 175

9.6 Chemistry in Space ...................................................... 176

9.7 Chemical Cosmogony and Interstellar Molecules ........................... 178

9.8 The Emergence of Cosmochemistry ......................................... 180

9.9 Conclusion .............................................................. 183

References and Notes .................................................... 183

Part III

Solid State Chemistry and Biotechnology

10. Between the Living State and the Solid State:

Chemistry in a Changing World ........................................... 193

Peter J. T. Morris

10.1 Biotechnology and the Myth of a Recent "Biotech Revolution" ............. 194

10.2 Polymer Science ......................................................... 195

10.3 At the Boundaries ....................................................... 196

10.4 A Composite Field of Research ........................................... 198

10.5 Conclusion .............................................................. 200

References and Notes .................................................... 200

11. Biotechnology Before the "Biotech Revolution": Life Scientists,

Chemists and Product Development in 1930s—1940s America ................. 201

Nicolas Rasmussen

11.1 Hormones: "Master Molecules" of Life Between the Wars ................... 203

11.2 Pharmaceuticals in Peace and War ........................................ 210

11.3 Conclusion .............................................................. 218

References and Notes .................................................... 224

12. Polymer Science: From Organic Chemistry to an

Interdisciplinary Science ............................................... 228

Yasu Furukawa

12.1 Macromolecular Chemistry as a New Branch of Organic

Chemistry ............................................................... 229

12.2 From Macromolecular Chemistry to Polymer Science: Staudinger, Mark,

and the Naming of a Discipline .......................................... 231

12.3 The Rise of Polymer Physics ............................................. 233

12.4 The Biological Nexus .................................................... 237

12.5 The Problem of Interdisciplinary Science ................................ 238

12.6 Polymer Science versus Macromolecular Science: Continuing

Strife .................................................................. 240

References and Notes .................................................... 241

13. At the Boundaries: Michael Polanyi‘s Work on Surfaces

and the Solid State ..................................................... 246

Mary Jo Nye

13.1 Polanyi on Scientific Ideals and Scientific Practice .................... 246

13.2 The Potential Theory of Adsorption, 1914—1932 ........................... 248

13.3 Diffraction and the Solid State ......................................... 250

13.4 Rewards and Recognition in the Scientific Community ..................... 252

References and Notes .................................................... 254

14. The New Science of Materials: A Composite Field of Research ............. 258

Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent

14.1 From Metallurgy to Solid State Physics .................................. 259

14.2 From Reinforced Plastics to Composite Materials ......................... 262

14.3 From Composite to Complex Structures ... Through Biomimetics ............ 266

14.4 A Future for Chemists? .................................................. 267

References and Notes .................................................... 269

Index ................................................................... 271